Let’s do a little free association. When you think about the Pacific Northwest, what do you think of?

Rain, yes, point for you. Mountains, mmhm, good. Salmon! Definitely. You in the back–wet, you say? Well that’s redundant with “rain,” but yes…

You know what no one says? Chili peppers. Chili peppers are not associated with the PNW. Not culturally, not climatologically, not historically, not culinarily. Chili peppers require sun and heat, and lots of it for many days in a row. It’s really hard to grow chili peppers in the PNW.

But I did it.

For the first time, I successfully grew chili peppers in our garden! I planted them as starts in early June (which is when the soil finally warms up around here), and kept them covered under plastic for the rest of the month so they wouldn’t be stunted by the cold nights–my downfall in previous attempts. By August, I had some peppers. Interestingly, I found that they ripened in an order that was pretty closely tied to their rank on the Scoville scale.

First the sweet peppers ripened, followed quickly by poblanos, then jalapenos. The padron peppers started to ripen around the same time as the jalepenos. If you’ve never heard of padron peppers (pimiento de padrón), they are a dangerous but less-deadly game of Russian Roulette: 9 out of 10 padron peppers are mild and sweet. But 1 out of 10 is as hot as a thai chili–around 50,000 heat units, if you’re keeping track. And the kicker is that you can’t tell until you taste it. Capsaicin roulette is a fun game to play on a summer evening if you need a pick-me-up. I once tossed a chopped padron into a stir fry without tasting in advance, and shortly found that I couldn’t breathe in my kitchen due to the spice. Yeah, they’re fun.

After the padrons, there was a lull; I had 3 truly spicy varieties, and they were slowly, slowly maturing. By early September, a couple of cayenne peppers started to turn red, and by late September, the thai chilis slowly shifted from green to orange. But the habaneros remained tiny–the largest just a half an inch–and they were steadfastly green. By October the nights were getting cool, so I extended the season with a plastic cover and PVC hoops over the peppers. I thought it was worth seeing if I could eek a few more off the plants.

And wow! What success. Although we had some raging wind storms in October, the thai peppers and habaneros speedily ripened under their shelter, and I ended up with approximately 5 ripe habaneros, and handfuls of thai chilis.

If you live in the south, stop laughing. 5 ripe habaneros is a big deal.

The whole point of going to great length to grow chili peppers is hot sauce, IMO. I love hot sauce. In my kitchen, hot sauce goes on eggs, in soup, on steak, roasts, casseroles, pasta, sauteed veggies, and pretty much anything savory. And yes I know that Tobasco sauce is available in every supermarket and costs only a couple of bucks a bottle, but it’s not in the spirit of local, micro, or craft (but I’m going to come back to it).

In the end I probably ended up with 2 lb of spicy peppers. It’s not much, but for the PNW it’s a victory, and it was enough to try 3 different recipes for hot sauce.

1. Fermented Hot Sauce

Josh and I love all things fermented, so it seemed an obvious choice to make a fermented hot sauce. But fermented hot sauce has a long lead time, and anytime you’re working with fermentation, you do have a risk of losing your batch to unfriendly bacteria. So I didn’t want to put all of my precious peppers into fermented salsa. I just made a quart, and set it in the cool basement to ferment for 2 months with an airlock.

2. Asian Hot Sauce

Inspired by a modest glut of thai chili peppers, I wanted a recipe that would tip its hat to them with umami flavors of fish sauce and a hint of sweet. This recipe also called for roasting the chilis, which was different than the other 2 recipes.

3. Hot Sauce in a Hurry

This recipe was actually the first one I made in early September, when everything was ripe and ready to pick and needed to be processed, and the promise of a 15-minute anything got my attention. This recipe is vinegary and vibrant, and due to the fact that I made it primarily with cayenne and padron chilis, it’s also just medium-spicy, which is nice when you don’t feel like being punched in the mouth by your dinner.

The verdict? Fermented hot sauce by a mile! It’s savory, and umami, and YES spicy, but also rich and tangy and oh so good. Next year I’ll probably only do fermented hot sauce, maybe even experimenting with different lengths of fermentation: 3 months, 6, even 12 if I can stand it.

Which brings me back to Tobasco sauce. Yep, you can find it in every neighborhood diner. It’s the most recognizable hot sauce brand in the U.S., and it’s an enormous corporate-made product. But here are a few more interesting tidbits about Tobasco sauce:

- Although huge, it’s still a family-owned business (though some have compared it to the Godfather, so it’s up to you whether this is on the plus list or the minus list)

- There are only 3 ingredients: tobasco peppers, vinegar, and salt. These are the same 3 ingredients, and in the same ratio, that have been used since the recipe was developed before the Civil War.

- The peppers are picked by hand—not machine.

- It’s fermented for three years in used bourbon barrels prior to bottling.

- I’m just going to repeat #4 because wow. It’s fermented for three years in used bourbon barrels.

- The byproduct from the milling process (when they strain out the solids) is used in muscle rub products, like Ben-Gay, so it’s a make-no-waste sort of product.

- The labels, caps, and bottles for Tobasco sauce are all made in Louisiana, within a 2.5 hour drive from the sauce facility. So it’s actually the embodiment of the local food movement.

So, respect, Tobasco. Respect.

If you want to read more:

http://www.seriouseats.com/2013/10/behind-the-scenes-making-tabasco-sauce-avery-island-la.html

Mt. Baker can be seen towering above one or two if you get the right perspective and serves as a stun-you-back-to-the-moment sort of view, especially at sunset.

Mt. Baker can be seen towering above one or two if you get the right perspective and serves as a stun-you-back-to-the-moment sort of view, especially at sunset.

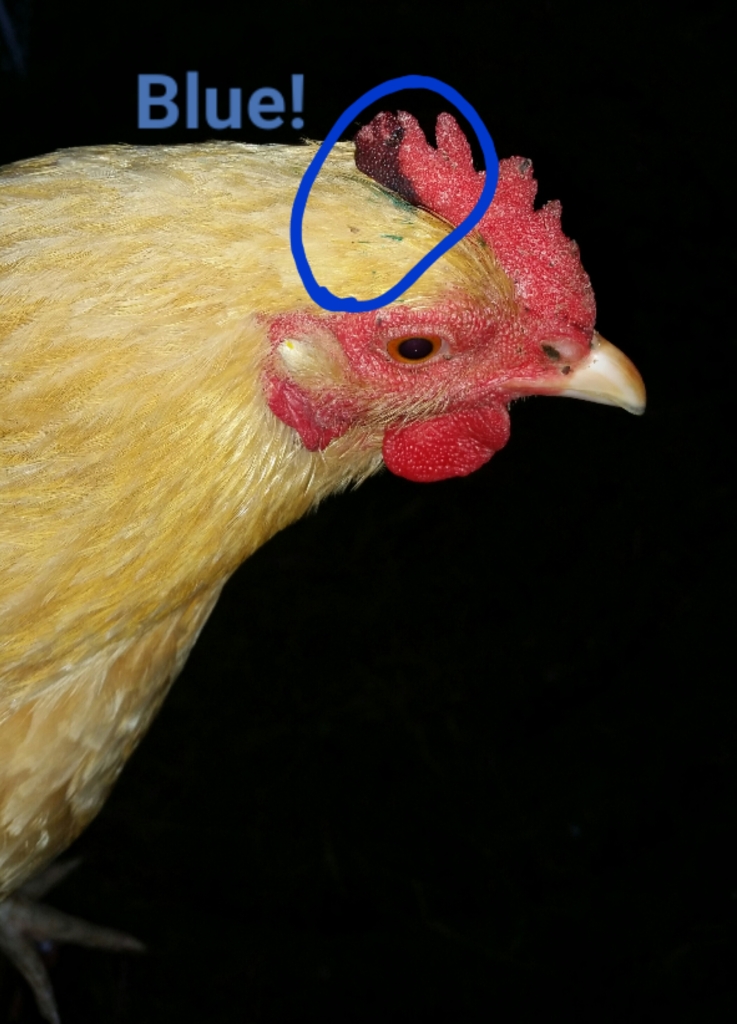

To speed things up, we rented a heavy duty tiller, since the pasture had finally dried enough to use it. (We also used it to repair a large over-used weedy paddock while we had it). Then, the best tillers of all got involved to finish it off: the chickens. We put 6 hens in the portable chicken tractor and moved it daily for another week.

To speed things up, we rented a heavy duty tiller, since the pasture had finally dried enough to use it. (We also used it to repair a large over-used weedy paddock while we had it). Then, the best tillers of all got involved to finish it off: the chickens. We put 6 hens in the portable chicken tractor and moved it daily for another week. With the soil finally friable to a few inches, I raked it into raised beds. Then, I mulched the pathways with bog rush–a reedy and otherwise useless (to my knowledge) plant that takes a long time to break down. I also lined the steep bed edges with scythed grass clippings to retain moisture and keep down weed pressure.

With the soil finally friable to a few inches, I raked it into raised beds. Then, I mulched the pathways with bog rush–a reedy and otherwise useless (to my knowledge) plant that takes a long time to break down. I also lined the steep bed edges with scythed grass clippings to retain moisture and keep down weed pressure.